Dr. Karel Martens is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology (Haifa, Israel) and at the Institute for Management Research, Radboud University (Nijmegen, the Netherlands).

Dr. Martens’ recent book: Transport Justice: Designing Fair Transportation Systems, has been recognized as revolutionary and seminal by many in the Transport Justice field.

You can watch his lecture at the inaugural Mobilizing Justice workshop, Nov 7th, 2019 at the University of Toronto, Scarborough in the video below.

Lecture Highlights

As the title suggests, according to Martens, to promote Transport Justice we must start by accurately measuring transport problems.

He starts with an analogy with other engineering fields who designed urban network systems (water, electricity, sewage, gas). He explains how their goal was to connect every household to provide those services for everybody. Transport engineering is late in the game, starting a few decades later compared to other urban networks. But it followed the same logic. One car for every household to give everyone access.

Even if we ignore that, in this “inclusive” plan, one car meant that the man of the house would drive (forget about women and children), things didn’t go according to plan as humans behave very differently than physical elements such as gas and water. Also, to be able to use the network as a car driver was never affordable or accessible.

There is no single mode of transportation that doesn’t exclude people.

Karel Martens

Despite initial good intentions, traditional transport planning tends to favor the affluent, focusing on infrastructure improvements that primarily benefit those with higher income levels. This bias often results in inequitable transport systems where the needs of disadvantaged groups, such as low-income individuals, the elderly, and people with disabilities, are overlooked (there are other equity-seeking groups, but those are the groups that Martens mentions in his presentation). Martens emphasizes that addressing this bias is the first step towards achieving transport justice.

The Importance of Accurate Measurement

Martens argues that to address transport inequities effectively, we must start by measuring who is affected by transport problems and how. Accurate measurement involves collecting data on various aspects of transport accessibility and mobility, such as:

- the quality and convenience of trips,

- availability of public transport options,

- the cost of travel,

- unrealized trips and

- the time required to reach essential services.

This data can highlight disparities and guide policymakers in crafting targeted interventions. In order to achieve that, Martens proposes three possibilities for measurement:

- Trip Pattern Analysis

- Accessibility Levels

- Direct Measurement

1. Trip Pattern Analysis

The first option is to use already available data about traffic volume, public transit usage coupled with data about where people travel from and to. By analysing those patterns along with socio-demographic, we can start to figure out who is being excluded and what they are missing.

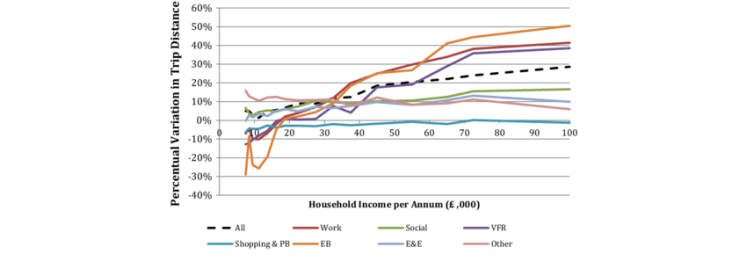

One example is a paper from 2016 (Lucas et al.) showing the relationship between level of income and number/distance of trips (VFR: Visiting Friends and Relatives, PB: Personal Business, EB: Employer’s Business, E&E: Escort and Education).

Higher incomes correlate with higher mobility (see figure 1 and 2 above). As we will see in future posts, differences in mobility levels within a population are acceptable from a transport justice perspective, within certain limits.

Another example is a paper from 2010 (Roorda et al.) that investigates the relationship between modes of transportation and vulnerable groups in Canadian cities. One of their findings was that while car ownership can generate a significant number of trips for elderly people it might have the opposite effect to low income families. In other words, owning a car can reduce people’s mobility.

Martens is cautious about this option since it needs to be analysed within a broader context. It depends on “where you live, the type of job you have, your household composition or the type of person you are.”

Longer trips, for example, are not necessarily a positive outcome. Someone living in a compact city where they can access multiple destinations on short walks make shorter trips might have higher quality of living than a person that needs to commute across the city just to get to work every day. Housing and the ability to choose where one lives is also an integral part of Transport Justice conversations.

In essence, the question “When are less and/or shorter trips a problem?” doesn’t have an straightforward answer.

2. Accessibility Levels

This alternative is the core thesis on the Transport Justice book. The reasoning is that accessibility is a good proxy for freedom, independence and a self-fulfilling life. A high level of accessibility gives you more job opportunities, more choices to health care (should you ever need any) and more social connections. You don’t have to take advantage of each and every one of them, but you are not restrained, you are free to choose when you have high accessibility levels. This approach addresses both actual and potential mobility.

Every person is entitled to a sufficient level of accessibility (under virtually all circumstances).

Karel Martens

One example of how this can be measured is a study done in Amsterdam (van der Veen et al., 2020) looking at the accessibility (destinations available within a delimited area) and potential mobility (ability to get to those destinations under a specific amount of time). As we can see in Figure 3 below. Bikes have very low potential mobility but still a moderate accessibility level. Public transit has much higher potential mobility but lower accessibility and cars have the highest accessibility and potential mobility even considered peak hours with traffic congestion.

Based on Martens’ statement above, a transport problem is basically an insufficient level of accessibility. The study uses the average measure for cars at peak time as a threshold for both variables. However, Martens is clear that what entails a sufficient accessibility level varies from place to place and should be primarily a political decision. It can be informed by surveys and data but it’s not a technical question.

Even though transport planning and policies don’t use thresholds, this is not a new concept. Thresholds are applied in other areas that provide basic social goods such as income (minimum wage), education (free public schools) or health (access to products and services).

3. Direct Measurement

An emerging third alternative considers issues that might not be captured from a purely spatial analysis. There are personal and socio-cultural reasons that might prevent people to access places. Fear, racism, social norms, mental health issues, among others.

Martens proposes to ask people directly. There are lots of surveys about travel behaviour. There could be a simple scalable survey about transport problems. But he would call it the Freedom of Mobility Survey, because it has a more positive ring to it. A survey that could capture not only the types of problems, but also measure the severity and frequency of those problems. According to Martens, there is already a body of literature adopting this approach, however it’s largely ignored by practitioners. The three main topics covered in such a survey would be:

- Satisfaction – Did you enjoy your trip?

- Autonomy – Do you rely on someone else to do the trip?

- Freedom – Can you do all the trips that you need and/or want to do?

Shifting to Inclusive Planning

Inclusive planning requires a fundamental shift in focus from infrastructure to accessibility and mobility needs. Instead of prioritizing road expansions and new highways, planners should consider how to improve access to transportation for all societal groups. This shift involves designing transport systems that are not only efficient but also equitable and inclusive.