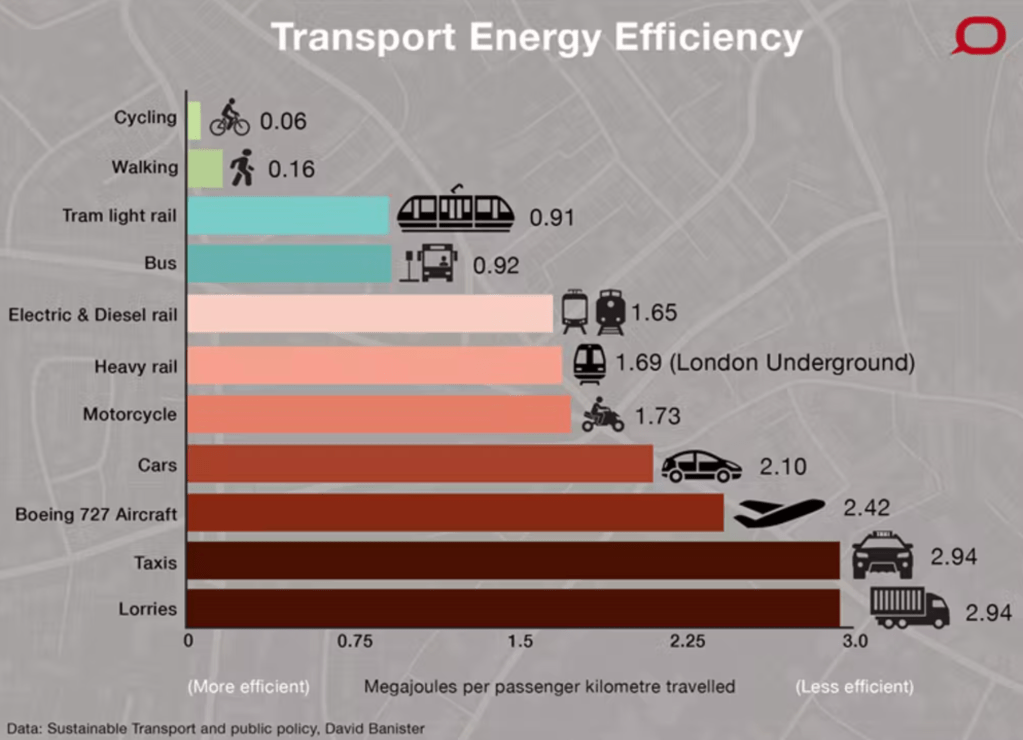

Cycling is the most energy-efficient form of transport ever used by humans, requiring between one third to one half of the energy required for walking the same distance.

Which transport is the fairest of them all? – The Conversation

The book Bicycling Science (published by MIT press) shows that in ideal conditions (mild temperature, low air drag, high performance bicycle and low-weight rider), a cyclist can ride over 550km using the amount of energy contained in one liter of gasoline. Using a more conservative calculation based on average conditions, the website Wikiwand shows that a cyclist can ride approximately 312km using the amount of energy contained in one liter of gasoline.

This is a limited analysis, restricted to the actual travel time and generally referred to as tailpipe emissions. It’s also the most commonly used. More comprehensive approaches would also consider the amount of energy required to produce the fuel (food or gasoline) known as well-to-wheel emissions; the vehicle (car, bicycle) known as cradle-to-grave or life cycle emissions; and the infrastructure itself known as systemic or network emissions. Those models would provide a much more accurate picture in terms of energy use since they take into account the necessary conditions for the travel to be possible in the first place. That would increase the energy efficiency gap between a bicycle and a car significantly.

Energy is a defining aspect of human civilization. What we can accomplish is bounded by how much energy we have available.

Yet, energy efficiency is only part of the answer to address our energy challenge. No matter how efficient we are, with an ever increasing demand there will be a limit to energy availability. There is an additional catch when energy efficiency is the only and ultimate goal. According to the Jevons paradox, increasing efficiency increases consumption since the cost tends to be lower due to higher efficiency. This scenario can bring us faster to the breaking point.

Even some renewables have a limit to ever-growing demand. It is crucial to prioritize choices that create a real reduction in energy use and use reliable and readily available renewable sources.

As we saw above. Cycling requires only 3-5% of the energy used for cars and it is human powered. A renewable energy that will be available as long as we exist and requires no additional infrastructure to be produced.

We are about to enter a new era in which, each year, less net energy will be available to humankind, regardless of our efforts or choices. The real choice we will have will be how we adjust to this new regime. That choice – not whether, but how to reduce energy usage and make a transition to renewable alternatives – will have profound ethical and political ramifications.

Richard Heinberg